Do you want to capture jaw-dropping Milky Way photos?

Of course you do! So let’s get you started with the need-to-know about Milky Way photography.

Co-authored by Cory Schmitz

If you’re brand-new to astrophotography and night-sky photography, it is highly recommended to start with our article on beginner astrophotography.

If you’re brand-new to astrophotography and night-sky photography, it is highly recommended to start with our article on beginner astrophotography.

We’ve created a video of everything you need to know to get started! Astronomy basics, the camera settings you need to know for astrophotography, and even some editing examples!

Now let’s get started…

1 Get the right shoot location

An essential to capturing great Milky Way photos is getting far away from city lights. The darker the better!

To reveal the faint structures in the galaxy core, long exposures are required. We’re looking at 10-30 second exposures (focal length dependent).

But not all light is bad, especially if you want to capture the surrounding landscape. While it’s always advised to shoot during new moon (no moon) in order to get the darkest skies, shooting when there is a thin crescent will provide enough lighting for the foreground.

Before heading out always check what the phase of the moon is. Too much moonlight will result in not much detail in the Milky Way and a foreground that looks like daytime.

2 Find the Milky Way core

The core is visible in the sky differently depending where you are around the globe.

In the northern hemisphere the galaxy core rises towards the southeast, moving southwest along the horizon.

In the southern hemisphere it rises towards the east, moving directly overhead — a glorious sight!

It’s important to know that the core isn’t visible all year round, and that’s the reason April-September is fondly known as Milky Way season.

The easiest way to find out where and when it will appear, is by using a planetarium application, such as Stellarium (free), which allows you to select your location, date, and time. You can change the date and time toggles to get an exact idea of how the core will appear in your location and when best to shoot it.

Stellarium is a free open-source planetarium application for your computer. It shows a realistic sky, similar to what you see with the naked eye, binoculars, or a telescope. It is currently being used in planetarium projectors. (source: Stellarium.org)

Other smartphone apps like PhotoPills enable an augmented-reality overlay where you can frame your composition on your phone, with date and time toggles that will show you exactly where the Milky Way will appear in your frame. If you just want to see where the Milky Way will be in the sky, you can also check out smartphone apps like SkySafari, Star Walk, Sky Guide, or Stellarium Mobile Sky Map.

3 Compose your photo

Framing a photo for nightscapes is very similar to landscape composition, with the main difference in framing to have the Milky Way visible in your frame — so a little more sky than usual.

The key to successful Milky Way photography is using landscape elements and the sky to build a balanced photo. The same basic principle of the rule of thirds can be applied to your night scene.

Use your foreground to tell a story. You can also use objects in your foreground to relate the size and scale of the sky – like silhouettes of people.

4 Use the right equipment

Don’t neglect the basics!

Don’t neglect the basics!

A good sturdy tripod is a must. The best tripod head choice is a ball head that allows for 90 degree rotation.

Sufficient memory cards and 1 or 2 backup batteries (keeping in mind that battery life is shorter in cold conditions).

Using a remote shutter release cable (or a 2-second shutter delay) on your camera will minimise vibrations that can ruin your exposure.

…and don’t forget a nifty red LED headlamp!

As for your camera, make sure you know the ins and outs of using it in manual mode – we’ll discuss camera settings in more detail in step 5. When working with such sensitive light sources like stars, the camera (doesn’t matter how top of the range) cannot select the correct exposure settings!

What lens should you use?

The best lens choice for capturing the Milky Way is a fast (f/2,8 or better) wide-angle lens. Anything from 10mm (or fisheye) to 24mm will produce great results. Most photographers settle around 20-30mm, but even at 50mm you can photograph great up-close image of the core.

5 Use the correct camera settings

Exposure of actual light to the sensor is controlled by the shutter speed and aperture, these two settings control how much light reaches your sensor and for how long.

ISO is the camera sensor’s sensitivity to light, specifically the gain, or electrical amplification, of the sensor.

Great photos are possible when you understand how these three relate to each other in low-light conditions.

Your camera needs to be set to manual mode. If you don’t know how to set the following features we suggest some further reading on the manual operations of your specific camera.

Setting aperture

This is lens dependent. Since we want to gather as much light as possible in a short space of time, the wider the better. Most lenses are f/4 or f/2,8 – work with what your lens allows. Some advice for those fast lenses like f/1,8 – you’ll get better results by stopping the lens down to f/2,8. Shooting too wide on some of these can cause blooming & chromatic aberration to show itself.

Selecting the shutter speed

Your exposure time is dependent an a variety of factors.

Firstly, what is the focal length of your lens? Have you ever heard of the “rule of 500”? In basic terms, it’s an equation that uses your focal length to determine the maximum amount of exposure time for your sensor size and focal length before the stars start to trail.

Example: 500 divided by focal length (let’s say 24mm)

500 / 24 = 21 seconds

But, it’s not always perfect, which is why we wrote this post on how to expose for perfect stars. You should also take into account your sensor size, is it crop (APS-C) or full frame?

ISO

Understanding ISO

ISO is the sensitivity of the camera’s sensor to the available light.

When the ISO is increased, your sensor is more sensitive to low-light conditions. You’ll find that the higher the quality of the camera’s sensor – the better low-light photography it is capable of. The drawback of imaging at higher ISO levels is increased noise, but the better the sensor quality, the less noise it will have at higher ISO settings.

ISO settings for night photography are location and sensor dependent. Mostly a setting of 800 / 1600 / 3200 or 6400 is used. Some photographers even push as high as ISO 12800 on shorter exposures like 10seconds.

Selecting the right ISO comes down to testing what works for your location, your lens and camera. We suggest starting at ISO 1600 and do test exposures.

Other settings

Raw format:

Raw format:

Always shoot raw! Raw format offers the best quality for your photos. Shooting in low-light levels require you to push your DSLR to the best it’s capable of. There is a much larger dynamic range (12-14 bit) in raw images vs. JPG (8 bit). When shooting the night sky, utilising more dynamic range always allows for better photographs and more details. Much of what we are photographing is very dim, and difference between JPG and raw really shows itself in the post-processing steps!

White balance: (Or colour temperature)

Night-sky photography doesn’t share the same settings as daytime, and color temperature can range from about 2900-4400K. Selecting the right white balance for your photo is also very much dependent on your location — read more about white balance here. Thankfully when you’re shooting in raw format, you can always change the colour temperature in post production.

In-camera noise reduction:

Using in-camera noise reduction disables the DSLR for the same length of time as the light exposure. With great noise reduction post-processing techniques available today, noise is best dealt with afterwards, but you can use this at your discretion. (It’s essential to switch off in-camera noise reduction when shooting star trails)

High-ISO noise reduction:

If your camera has this setting, it is recommended you use it! With Milky Way photography you are always shooting at high ISO, so you might need a little more help! Again — use at your discretion.

6 Process your photo

Taking a good photo is one thing, making the Milky Way ‘pop’ is another. Too often we judge a good photo on the camera’s sensor quality, where in reality, great post-processing skills can drastically close the gap between an average and superior camera sensor.

For impressive Milky Way images, you’ll have to focus on editing specific elements in the photo.

Note: these are the basic recommended settings, many astrophotographers choose to edit more finer details.

General photo adjustments

- Exposure adjustments and white balance corrections

- Clarity (in LightRoom), A.K.A. local contrast

- Midtone adjustments and enhancing highlights using curves

- Adding contrast

- Increasing saturation

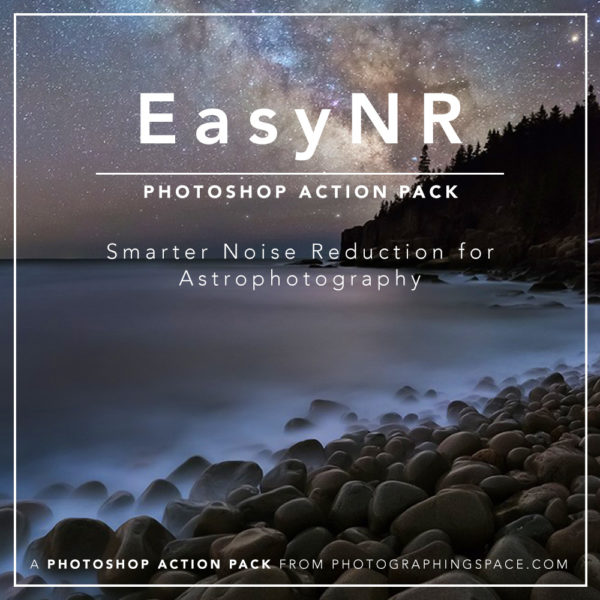

- Noise reduction (read: our tutorial on noise reduction in LightRoom)

- Sharpening (read: some tips about sharpening in LightRoom)

LightRoom user? Get more info: 3 powerful adjustments that will help you make your Milky Way pop

7 Advanced processing techniques

Selective Adjustments

To bring the Milky Way core out even more, some selective adjustments often need to be made. These can be done using selective brushes or masks to isolate the selection to the core itself. Regardless of your preferred image editor, these settings are universal – work with the option that your most comfortable with, for example — using layer masks in Photoshop.

When you have the core selected (we recommend that your selection is well feathered) some of the following adjustments will help bring out some more detail.

These general settings will go a long way in improving your Milky Way core edit:

- Consider lifting the tint or the white balance of the core itself – ever so slightly. A slightly warmer core brings out the tones nicely.

- Add more contrast.

- Lift the exposure slightly.

- Increase saturation slightly.

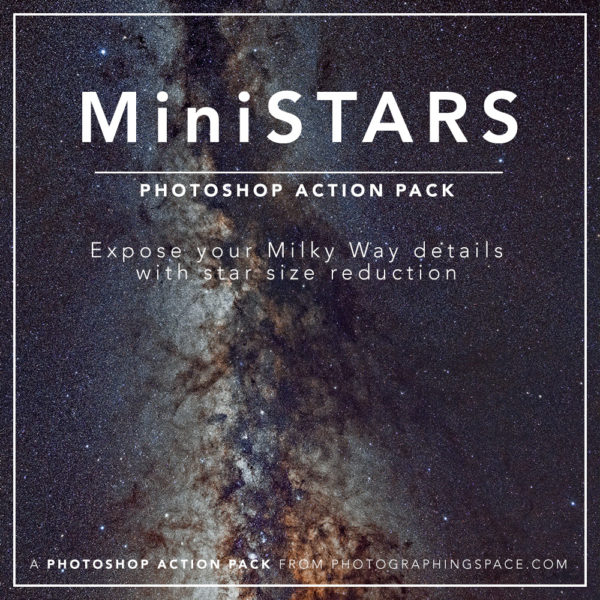

Star reduction

In addition, what undoubtably works extremely well is star reduction, as it ensures that the core does not get lost among the millions of stars visible in your photo.

Stacking multiple exposures

One of the best ways to increase the quality and detail of the Milky Way photos is to take multiple exposures of the exact same frame and “stack” them in post-processing with specialised software that aligns and layers the exposures on top of each other. The software computes an average of the aligned pixels to increase signal-to-noise ratio of the final image. This drastically decreases noise, while allowing you to bring out further detail in the faint Milky Way structures.

Want to give stacking a try? Check out this article with raw Milky Way images to download and play with!

Great informative article thank you so much! Loved reading it .? I’m going to read all the other articles to and will try out what I’ve read !!

Love your photos !!!

Thank you! Yip – there are a lot of resources on the site. Please tag/share your results with us!

I assume there are tutorials,

Perhaps even personalized weekend

Workshops to teach Lightroom to the technologically challenged.

Hi Larry,

Yes there are tutorials out there about the basics of Lightroom, which are very good to learn before diving into editing astrophotography images!

Best of luck,

Cory

You need to update your tutorial. Stellarium is no longer free, at least through the Google Play Store for use on Android phones. Do you have another suggestion?

Thanks for the heads up, Zorba! I’ve updated the tutorial with some other application options for mobile. However, Stellarium is also an excellent choice and well worth the cheap price they put on it for the work the authors put into it.

Cheers,

Cory

That is true Zorba, but there is a web and a desktop version that are still free

Should we use a PC or Apple and photoshop or Lightroom .?

If a PC laptop, i5 or i7, how much ram , memory, optical or mechanical drive?

Ty

Tom

Hi Thomas,

So sorry this comment got missed!

For simple Milky Way photography, you are not really limited by the computer you use, as anything somewhat modern will be fine!

Cheers,

Cory

Great article, although I’ve been doing a fair bit of planetary imaging I recently got into DSO’s and galaxies and you are an inspiration for this discipline cheers, David

Hi David,

That’s great to know, and we are happy this is helpful for you!

Cheers,

Cory